How media literate are you? At Revealing Reality we’ve been thinking a lot about media literacy lately, and this is a question we’ve been asking ourselves. We’ve found thinking about how to ‘measure’ media literacy really interesting – and also quite personally challenging!

We found it useful to ask ourselves how we weighed up our own media literacy, what factors we took into account and how we measured them.

For example:

Thinking about how you appraise information, how you judge it to be truthful and accurate? What does this involve? Do you check its accuracy and veracity? If so, how? Do you go and read several articles on the same subject and compare them?

What about the author, or the website it’s published on? What clues or contextual information allow us to make quick and useful judgements?

Are you thinking about what device you’re accessing the information on and whether that might affect what you’re seeing? Or the platform you’re on, and how that might affect the content you’re being served?

What about your own biases and what you already know about a given subject? How does that affect the way you consume, interpret and apply information?

And, when all is said and done, how much can you be bothered? Double- or triple-checking everything is hard work, and you might have better things to do!

So what does being media literate really look like? One particular project has recently prompted us to think about it in detail. Given our ethnographic roots as an agency, we were excited to be awarded a commission by Ofcom to carry out an ethnographic exploration of media literacy. Called A day in the life, we did indeed carry out full-day ethnographies, plus follow-up diaries and interviews, with 20 participants across the UK, exploring and observing in real time the role media plays in 11 aspects of people’s lives and its relationship with their media literacy.

The research allowed for an in-depth exploration of the factors and characteristics that shape someone’s levels of media literacy, which we saw often varied in different aspects of their lives.

We saw that not only did people’s access to media and information affect their literacy, but even if they had the ability, skills and knowledge to access information, they were not always motivated to engage with it.

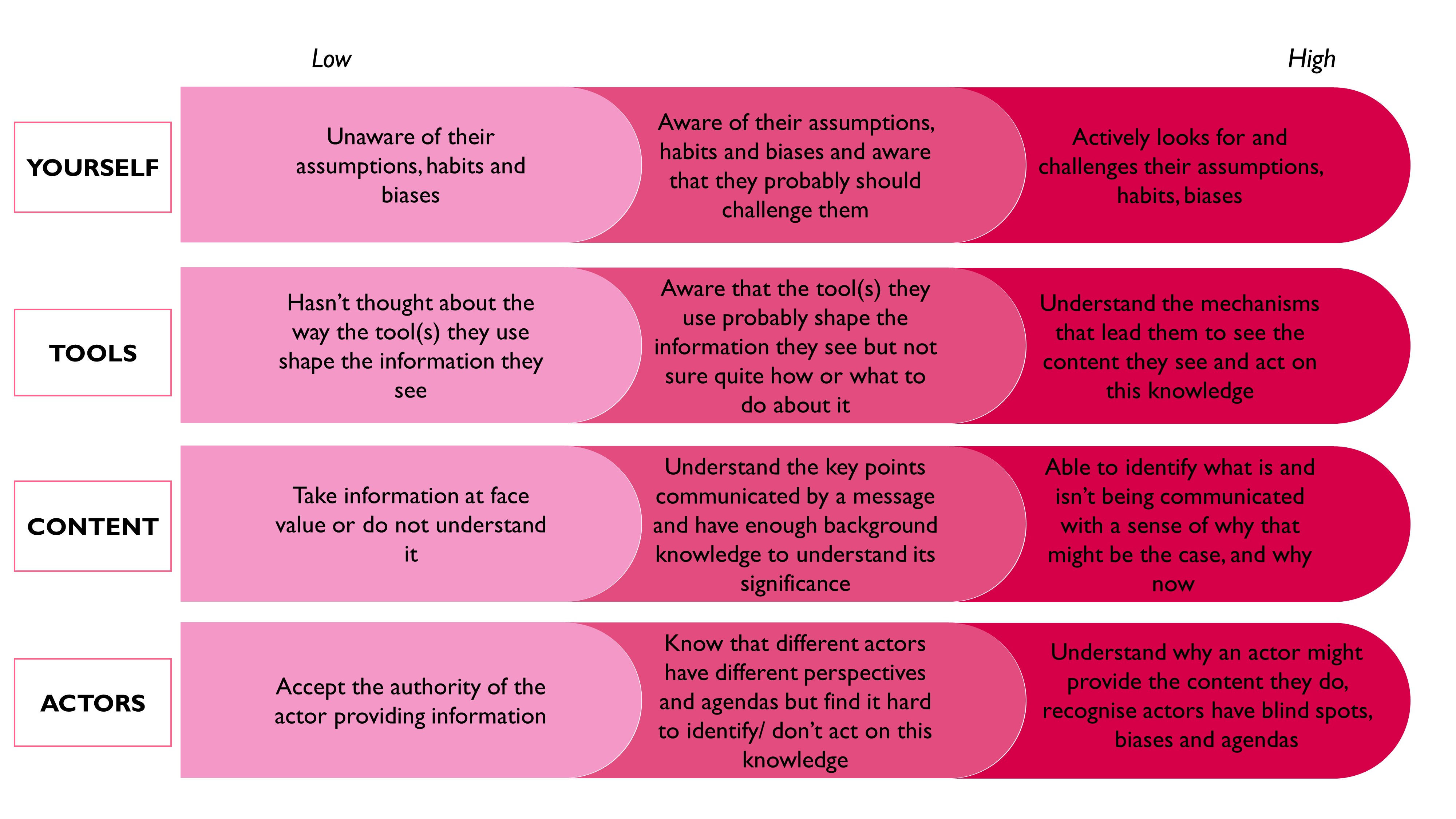

What’s more, even if people had access to information and were motivated to engage with it, media literacy depended on critical analysis not only of the content itself, but also how it was served (the tools), who it was made or promoted by (the actors) and the biases or preconceptions the consumer brought to it. For each of these aspects, we developed a spectrum of low to high capabilities (below).

We’ve found it impossible not to look at the model and ask ourselves where we sit on those spectrums. We’ve also been forced to admit that in some cases even if we had high capability, we may not always be motivated to use our skills and understanding – and indeed the level of marginal ‘extra’ media literacy we would gain would not in all cases be worth the effort or the opportunity cost. It’s been a fascinating and rewarding project, in which we’ve not only learned about the respondents, but also about ourselves!