When Ofcom first commissioned its longitudinal Children’s Media Lives study 10 years ago, several of the children in this year’s research weren’t yet born. It was 2014, later dubbed the “year of the selfie” in the wake of that year’s ice-bucket challenge, the #nomakeupselfie and the “selfie that broke Twitter”. A year of laughs, cold-water gasps, attempts at authenticity and a group of famous people who took their own picture at the Oscars.

Social media was a well-established force – already shaping culture as well as depicting it – for both children and adults. But among children, it was part of a mixed media diet. In 2014, most children had their own smartphone by the time they were 13. Many were on a pay-as-you-go contract, which limited how much media they consumed on them and what they used them for.

Ten years ago, the children in this study still watched TV – sometimes alone in their rooms, sometimes in their living rooms with their families. Some of them used Snapchat, mostly to send selfies and messages to close friends.

Roll on four years and in 2018 we found that some of the girls in the study were using Musical.ly, “a random stream of videos posted by other users, many of whom are strangers”. This user-generated content was “unpredictable” – ranging from “rehearsed dance routines or lip-synced videos, either made by amateurs or skilled contributors”, to “videos with sexual undertones”, “strong language” and “sexualised commentary”, which we reported could “make children feel uncomfortable if they came across something they didn’t like or understand”.

TikTok: from dance routines to media dominance

Here we are another six years later and this “random stream of videos posted by other users” is now the dominant media in most children’s lives. TikTok – as Musical.ly became – is where they go to learn about the world, about themselves, for culture and for comfort.

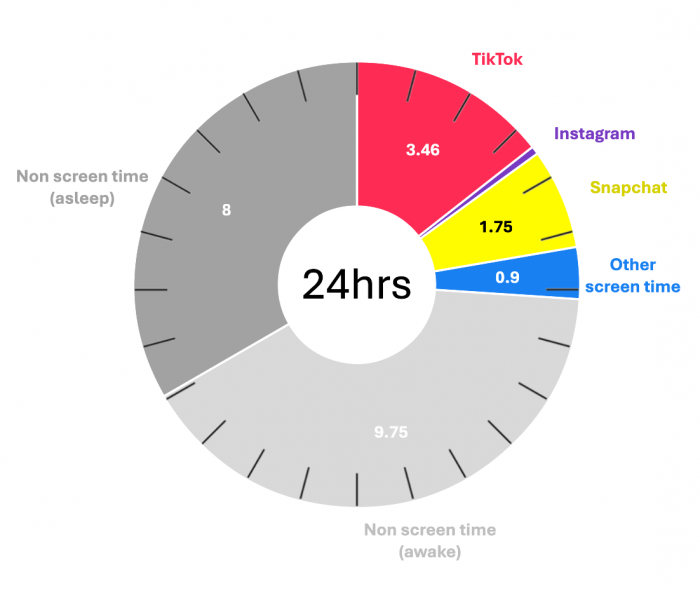

Now, most children get their own smartphone when they are nine or 10 and a quarter of three to four-year-olds have one. And on these phones, in this study we see children are mostly consuming media alone and via social media which may not be monitored by parents. In 2014, children reported to Ofcom they were spending 12 and a half hours a week online on average. In this year’s Children’s Media Lives, we see many of the children are spending six, seven, eight hours a day on social media – often more.

Unlike the content they used to watch on TV, often overseen by their parents, the videos children are watching on social media are largely unmediated by their parents or the platforms – what they see might be true, it might not. It might be good for them, it might not

Social media: visual, commercial, professional

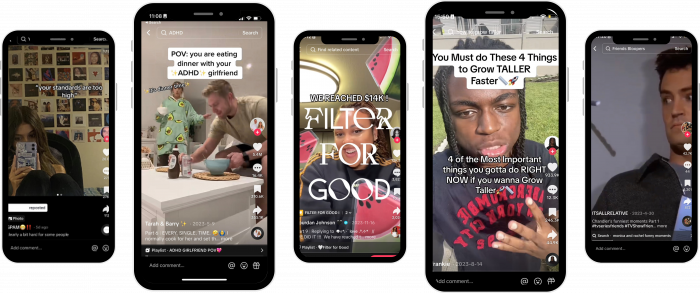

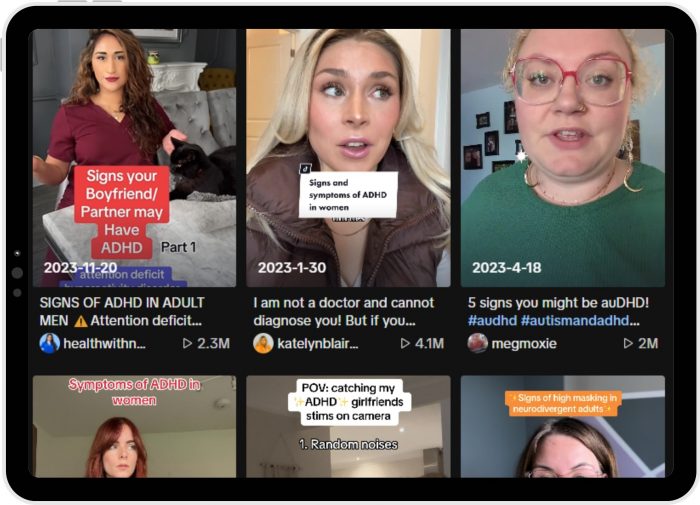

Over the last 10 years we’ve seen social media become less and less social. Children are primarily looking at visual media – images and videos – not interacting with other people. The content they see in their feeds is increasingly professionalised and commercialised – as social media has become bigger and bigger business, it’s changed the way people use it. Most of what children now see on social media was created by someone with the deliberate goal of capturing attention, garnering ‘likes’ or building a following – and it’s often their job to do this.

Video is the most popular media format and as we’ve seen this year, videos continue to get shorter, faster, more stimulating, and, in some cases, more intimate, all while what children are recommended on their feeds is ever more personalised.

Seeking out the sensory online

Of course, as with any experience in childhood, most children in our study can’t imagine life any other way. Some thought they would feel lonely without social media or gaming – it’s where they turn to satisfy their needs, meet their aspirations and feel connected to the world and other people.

Some of them go round to their friends’ ‘houses’ on Roblox because it’s easier than visiting them in person; they play football online; they get the instant gratification of watching dramatic short-form videos of people performing hyped-up challenges.

Children watch videos of slime, sludge, sand, hands playing with crayons, bubbles, food – mirroring but not directly experiencing the sensory and tactile nature of messy play and mud pies.

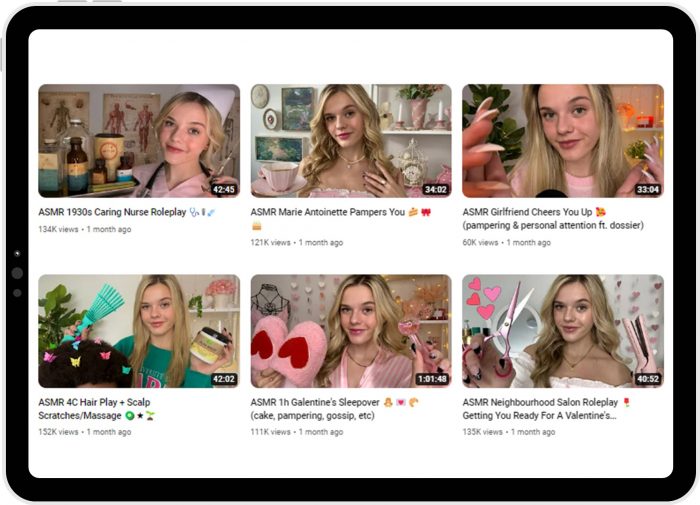

The role of role-play

This year we’ve seen more of the participants, especially the girls, watching ‘Get ready with me’, ‘Point of view’ and role-play videos. They tell us they are soothed by content creators who act like their best friends, their big sisters, their confidantes, who give them advice. The trend is towards heightened intimacy – often using ASMR tropes – someone giving them the sense they are whispering in their ear, playing with their hair, stroking their back. The children say they watch these videos to relax, or to help them go to sleep, but sometimes they stay up half the night watching one after another.

This is easy when the children’s social media feeds give them more of what they ‘want’. Platforms and content creators alike are extremely responsive to the trends that get them traction. Over the years, they have gone to greater and greater lengths to capture and keep users’ attention, even as the children themselves tell us they find it increasingly hard to focus on one thing or for long – a whole episode of a TV programme, for example. Last year children were watching two unrelated videos at once within split-screen TikTok formats, this year for the first time we’ve seen a triple-split-screen video – three videos playing simultaneously.

‘Watch to the end’

The children’s attention is being caught by hyper-stimulating videos that are loud, bright, dramatic and dizzying. If their interest starts to fade, they’re encouraged to wait for the ‘big reveal’, or they choose to watch the video at twice the speed so they can ‘get to’ the next one more quickly.

The children mostly say they enjoy the content they’re watching. But it doesn’t always look as though it’s genuinely meeting their needs. Some tell us they are often lonely, bored or anxious. And the time children spend on social media is time they’re not spending on other things. Over the years some have talked about the hobbies they’ve given up or the sports they’ve stopped playing, while simultaneously their screen-time has crept upwards, or they’ve shifted to scrolling social media alone in their bedrooms rather than watching TV with their family.

Truth, trust and the next 10 years

As in previous years, we also saw some of the children being quite clear they didn’t think certain types of content were ‘appropriate’ on social media, and several others reflecting that they knew what they were seeing on social media was one-sided and trying to find additional perspectives. They didn’t always know how or where to look, but some were trying to get beyond what they were being served on their feeds, work out what was true and where to find it.

Ten years ago, children’s media lives looked very different than they do today – but by looking back we can often see how one trend led to another. What will the next 10 years look like? Will children’s social media use peak? In another decade, the children in this year’s study will all be adults. What will they want their own children’s media lives to look like?