Helping children think critically about their online worlds

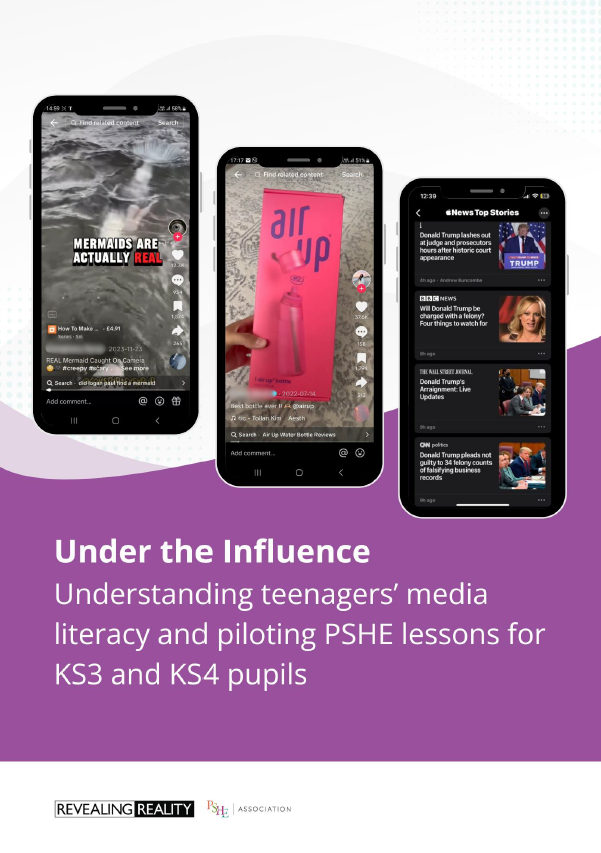

We have observed children’s changing relationship with the online world for over ten years through our longitudinal research for Ofcom, Children’s Media Lives. From social media feeds filled with friends’ faces donning silly animal filters, to this year, feeds filled with influencers where children can encounter four pieces of different marketing content in the space of 10 short seconds, what children see and how children use social media have changed dramatically.

Childhood itself, in many ways, is becoming a predominantly online experience as children encounter the wider world through their phone screens. Homework help, skincare routines, global news and even the exploration of self-identity are often filtered through social media feeds.

Today, young people’s worlds are less often shaped by teachers, textbooks or long-standing fables, and instead increasingly influenced by trending content, targeted ads, and viral videos. And what appears on their screen isn’t random. It’s driven by algorithms, designed to maximise clicks and retain engagement, and sell products.

For many children, the line between entertainment and information is increasingly blurred. Their feeds mix memes, adverts, news and opinion – all delivered in the same format, often by the same creators. In these spaces, commercial agendas are ever-present but rarely obvious, making it harder for children to recognise when they’re being sold to, influenced, or misled.

Content with high production value must be credible? Something with thousands of likes must be true? If an algorithm gives you more of the same, it must be helpful?

What children believe – and how they behave – is increasingly influenced by systems designed to keep them scrolling. Not to help them think.

Helping children become more critical of what they see

Teaching critical thinking is important. But knowing how to think critically doesn’t always mean children will – especially in the environment of their feed.

That’s why we partnered with the PSHE Association – to understand how children engage with their social media feeds and how to help them reflect more critically on what they’re seeing.

Together, we designed and tested a series of schools-based lessons grounded in young people’s actual experiences online from interviews and diary tasks with 20 young people.

Many of the children we spoke to could tell you what a sponsored post is. But when the message came from someone they liked – a favourite influencer or familiar creator – and featured many ‘likes’, very few considered the commercial agenda behind the content.

Their trust was often shaped more by tone and style than by source. A professional-looking video meant credibility. High engagement meant something must be true.

The challenge isn’t just about whether children can think critically – but whether they feel motivated or equipped to do so in spaces designed for passive scrolling, not active reflection.

Developing lesson plans to support critical thinking

Lessons developed by the PSHE Association aimed to bridge this gap. The aim was to encourage children the tools to pause, question, and reflect – without losing touch with the reality of how they use and enjoy being online.

The lesson plans focused on:

- revealing commercial and influencer agendas

- challenging common misconceptions

- motivating students to apply critical thinking in everyday scrolling

Each activity was grounded in real examples from children’s feeds. Not imagined problems, but familiar patterns – friend vs. influencer, advert vs. opinion, truth vs. viral trend.

We knew from the outset that this wouldn’t be straightforward. Children’s perceptions of the online world are shaped by years of daily use and exposure to algorithmically curated content – content designed to entertain, persuade, and keep them scrolling. Changing those perceptions, and motivating children to think critically about what they see, isn’t something that can be achieved in a single lesson.

It was also clear that some teachers needed support. Some were less familiar with social media platforms, making them less confident about how to teach about platforms they didn’t use themselves. Others were regular users, which sometimes made it difficult to take a step back and reflect critically. These challenges underscored the need for carefully designed lessons – ones that are not only accessible for students, but practical and confidence-building for the people teaching them.

Multiple phases meant the lesson plans and feedback tools could iterated and improved. The evaluation drew on classroom observations and surveys and interviews with teachers and students to build a nuanced picture of how children engaged with the lessons and the messages that most resonated or sparked discussion.

Media literacy as a modern life skill

Media literacy is increasingly essential for navigating the digital world – not just as a protective skill, but as part of how children make sense of information, identity and influence.

Supporting critical thinking means more than just teaching skills – it requires approaches that reflect the realities of children’s online lives. Interventions need to start from where children are, recognising the complex and often contradictory nature of how they experience their feeds.

Read the full report to explore what we found, what we learned, and how we can help children navigate their feed with more confidence and critical perspective.